I came to Terence Rattigan’s 1952 play The Deep Blue Sea in a bit of a roundabout way – I saw the 2011 film adaptation starring Rachel Weisz, Tom Hiddleston and Simon Russell Beale which I adored, and it encouraged me to read the play. Over the years, I’ve revisited it multiple times and its become one of my favourites.

People who know me have found my taste in plays strange – I much prefer things with darker undertones and that are, at their core, about people and relationships; why we do the things we do and what makes us tick. The Deep Blue Sea has this tremendously poignant and truthful quality about how it explores these questions, and I think that’s why I’m so drawn to it. That in mind, I jumped at the chance to travel to Chichester a couple of weeks ago to see it, and loved that it was staged in the Minerva – the smaller of their two venues; it heightened both the intimacy and intensity of the piece and I was so grateful and happy the Minerva has provision for me to sit up front in my wheelchair!

It’s 1951. Ten months ago, Hester Collyer left her husband, esteemed high court judge Sir William Collyer to pursue an affair with dashing former RAF pilot, Freddie Page. One fateful night, Hester decides to take her own life. Discovered by her neighbours and facing scandal, both from her relationship and the failed attempt, Hester has to decide wether her life can still have meaning, amid the ramifications of her decision sending shockwaves through the men in her life.

The level of detail in Peter Mckintosh’s design is astonishing. He gives us the interior of Freddie and Hester’s Ladbroke Grove flat, every inch reminiscent of the period. Having the fourth wall missing so us as the audience are immediately looking into the flat is incredibly clever; it almost feels intrusive and the smaller stage space claustrophobic as we watch these characters wrestle with their feelings. The most striking element was the rubble littered around the stage as you walked in, evoking both the play’s post war setting and the sense of how these characters are each in their own ways, broken and fragmented. Natasha Chivers’ lighting is gorgeously evocative, as is Debbie Wiseman’s haunting score. Everything ties together in such a finessed, polished way that it enhances the quality of the performances; my favourite kind of design!

Given the intimate space, what I loved most about Paul Foster’s direction was how nuanced it is; I got the sense that every gesture and movement, however small was important. There’s tension constantly simmering away, but it also had moments of dry wit that were always well judged and balanced. And boy does he know how to get the best out of his cast…

Nancy Carroll gives a revelatory performance as Hester. She strikes me as a character who is struggling to find her individuality as she has been so long defined by her relationships with the men in her life, and yet she goes to great lengths to appear always poised and confident. The relationships she has, both with Freddie and William allow her to explore different sides of her personality: fiery and aware of her sexual power with her lover, while her conversations with her husband are more restrained, not allowing herself to look back. To watch Nancy go through all these emotions with such ease and intensity was extraordinary; I can’t recall a time when I was moved so deeply by a raw, poignant performance by a leading lady. The moments I loved best from her were the close of the first act, where after Freddie inadvertently discovers her suicide note, he leaves the flat, and she screams down the stairs after him, begging him not to leave her alone tonight. It’s so powerful because up until this point, she has been so in control, and then she simply isn’t anymore, and the latter part of the play is concerned with whether she can put herself back together. Therein we have my second favourite moment in the play, a scene towards the end where Hester is joined by Mr Miller. He says to her:

“Listen to me. To see yourself as the world sees you may be very brave, but it can also be very foolish. Why should you accept the world’s view of you as a weak willed neurotic – better dead than alive? What right have they to judge? To judge you they must have the capacity to feel as you feel. And who has? One in a thousand. You alone know how you have felt. And you alone know how unequal the battle has always been that your will has had to fight”.

This speech, along with some of Miller’s others in the scene moved me to tears, thanks tenfold to Matthew Cottle’s wise, muted strength. Miller and Hester form a curious sense of kinship, and to watch Nancy and Matthew play off each other, especially in this scene was really moving as it’s done with such sensitivity and grace.

Gerald Kyd is perfectly cast as Sir William. He brings such a quiet, moving intensity to the character and I was drawn to him throughout. He has one of my favourite dynamics in the play: as a judge he remarks that “the study of human nature is, after all, my profession”, and yet, later on, he admits to Hester that he: “is very inexperienced in matters of this kind” whilst trying to understand her motivations for her attempted suicide. It’s so clear that he wants to help her, to meaningfully connect, but doesn’t know how to do so. There’s an incredibly charged scene where Freddie, bitter, angry and drunk, comes back to the flat, and he eventually asks Sir William:

“Still love Hes?”

Watching Gerald react in that moment shiver down my spine, moreso when William admits to Hester:

“The answer to that question is yes, by the way”. Gerald has a tremendous gift for expressing so much with just a subtle change in voice or body language, and it’s fascinating watch him react to the other actors, and in some instances completely change the emotional dynamic of a scene and make it even more intense and moving. I hope to see more of him in future!

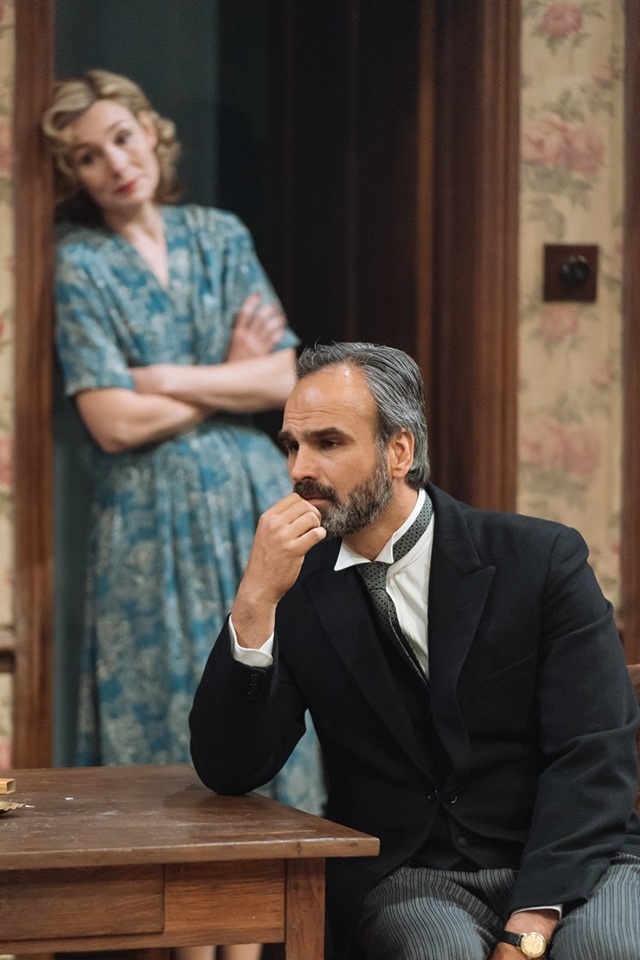

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan

With my exposure to the play first coming from the recent film, Freddie struck me as this dashing, romantic figure that you can easily see why Hester’s lust gets the better of her. Seeing the play, I understand now that Freddie is far more complex and interesting character than I gave him credit for. On the surface, he comes across a little boorish and arrogant, but as the play goes on, you learn that he’s struggling to adjust to civilian life, and see his pain. Much like Hester, I felt Freddie struggles to find his identity, and like Sir William, wants to connect but doesn’t really know how. Hester has a very telling line to describe him and the relationship they have, in conversation with William:

“Oh, but he can give me something in return, and even does, from time to time”

“What?”

“Himself.”

Where Sir William is assured and calm, Freddie is tormented, hiding behind his bravado and sarcastic wit. In Hadley Fraser’s hands, the latter becomes fragile and tender, yet always charming and charismatic – his portrayal is beautifully judged.

These three characters find themselves orbiting each other, pulled in by forces they are powerless against: love, lust and longing. To watch three incredible actors explore these dynamics and react to each other so intensely was incredible; by the end I was spent in the best kind of way!

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan

There’s brilliantly strong work from the ensemble cast as well; Denise Black all blustering warmth and wit as Mrs Elton, the landlady, and Ralph Davis and Helena Wilson as the nosy but well meaning neighbours, the Welches.

It was an absolute joy to see one of my favourite plays bought so vividly to life by a terrific cast and creative team; and I look forward to a fourth outing to Chichester very soon!

Pre show – SO ready!